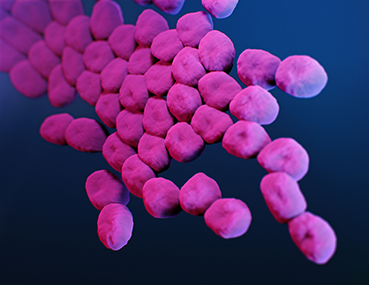

Cusabio Acinetobacter baumannii Recombinant

Abstract

Acinetobacter baumannii appears as an often multidrug-resistant nosocomial pathogen in hospitals around the world. Its remarkable persistence in the hospital environment is likely due to intrinsic and acquired resistance to disinfectants and antibiotics, tolerance to desiccation stress, ability to form biofilms, and possibly facilitated by surface-associated motility. Our attempts to elucidate surface-associated motility in A. baumannii revealed an inactivated mutant in a putative DNA-(adenine N6)-methyltransferase, designated A1S_0222 in strain ATCC 17978.

We recombinantly produced A1S_0222 as a glutathione S- transferase (GST). and purified it to near homogeneity through a combination of GST affinity chromatography, cation exchange chromatography, and PD-10 desalting column. Furthermore, we demonstrate A1S_0222-dependent adenine methylation at a GAATTC site. We propose the name AamA (Acinetobacteradenine methyltransferase A) in addition to the formal name M.AbaBGORF222P/M.Aba17978ORF8565P. Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) revealed that the protein is monomeric and has an extended and probably two-domain shape in solution.

Keywords: AamA; Acinetobacter baumannii; DNA-adenine-methyltransferase; E. coli; epigenetic; M.AbaBGORF222P; recombinant.

Acinetobacter baumannii Recombinant can cause infections of the blood, urinary tract, and lungs (pneumonia), or in wounds in other parts of the body. It can also “colonize” or live in a patient without causing infection or symptoms, especially in respiratory secretions (sputum) or open wounds.

These bacteria are constantly finding new ways to avoid the effects of the antibiotics used to treat the infections they cause. Antibiotic resistance occurs when germs no longer respond to antibiotics designed to kill them. If they develop resistance to the group of antibiotics called carbapenems, they become resistant to carbapenems. When they are resistant to multiple antibiotics, they are multiresistant. Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacters are often multidrug-resistant.

Who is at risk?

Acinetobacter infections usually occur in people in health care settings. People at higher risk include patients in hospitals, especially those who:

- are on breathing machines (ventilators)

- have devices such as catheters

- have open wounds from surgery

- are in intensive care units

- having long hospital stays

In the United States, Acinetobacter infections rarely occur outside of health care settings. However, people who have weakened immune systems, chronic lung disease, or diabetes may be more susceptible.

How is it spread?

Acinetobacter can live for long periods of time on shared environmental surfaces and equipment if not cleaned properly. Germs can spread from person to person through contact with these contaminated surfaces or equipment or through the person-to-person spread, often through contaminated hands.

How can you avoid getting an infection?

Patients and caregivers should:

- keeping your hands clean to avoid getting sick and spreading germs that can cause infections

- washing hands with soap and water or using an alcohol-based hand sanitiser, especially before and after treating wounds or touching a medical device

- remind healthcare providers and caregivers to wash their hands before touching the patient or handling medical devices

- allow healthcare staff to clean your room each day when you are in a healthcare setting

In addition to hand hygiene, health care providers should pay close attention to recommended infection control practices, including rigorous environmental cleaning (eg, cleaning patient rooms and shared equipment), to reduce the risk of spreading these germs to the patient.

How are these infections treated?

Acinetobacter infections are usually treated with antibiotics. To identify the best antibiotic to treat a specific infection, health care providers will send a sample (often called a culture) to the lab and test any bacteria that grow against a set of antibiotics to determine which ones are active against the germ. The provider will then select an antibiotic based on the activity of the antibiotic and other factors, such as possible side effects or drug interactions. Unfortunately, many Acinetobacter germs are resistant to many antibiotics, including carbapenems, making them difficult to treat with available antibiotics.

What is CDC doing to address Acinetobacter infections?

The CDC tracks the germ and the infections it can cause through its Emerging Infections Program. In addition, CDC works closely with partners, including public health departments, other federal agencies, health care providers, and patients, to prevent healthcare-associated infections and slow the spread of resistant germs.